The PA Turnpike was the first of its kind and received nationwide acclaim as an engineering marvel. It was touted as America’s First Superhighway when it opened on October 1, 1940, and was the national standard for superhighway design and engineering.

Today, the PA Turnpike stretches 565 miles. It continues its legacy of innovation in the ground-transportation industry and embraces modern-day technologies for faster response times, increased traffic flow, and safer trips for drivers.

As 2020 began, the country was aware of a new virus making its way to the United States. By March, the rapid transmission of a novel coronavirus, or COVID-19, led health and government officials to take unprecedented steps to

slow the spread. As states realized the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic many, including Pennsylvania, issued a Stay at Home Order directing all residents to shelter at home and limit movements outside of their homes beyond essential needs. Many

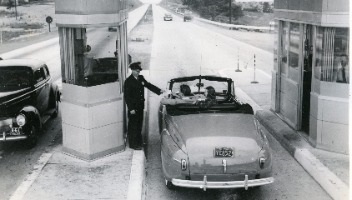

businesses were closed and employees who could work from home were instructed to do so. Toll Collectors were now at risk of being exposed to the virus while performing their jobs. The PA Turnpike decided to cease cash collections to protect employees

and customers and on March 16, 2020, converted to All-Electronic Tolling (AET). The original intent was to honor the AET conversion planned for October 2021 and return to a cash system collection system after the pandemic. No one could have known

the magnitude of the epidemic. PA Turnpike traffic plummeted by almost 50% by the end of May and revenues dropped by more than $100 million. On June 2, 2020, the PA Turnpike announced that it would permanently remain in AET. It was evident

that returning to a cash collection system was too risky. Several factors influenced the landmark decision. With drivers now accustomed to traveling through Toll Points without stopping, going back to a cash system would be dangerous for drivers and

toll collectors. If a collector were to test positive for the virus, the interchange would shut down leaving a gap in the ticket/cash system and the PA Turnpike could not operate under those circumstances.

As 2020 began, the country was aware of a new virus making its way to the United States. By March, the rapid transmission of a novel coronavirus, or COVID-19, led health and government officials to take unprecedented steps to

slow the spread. As states realized the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic many, including Pennsylvania, issued a Stay at Home Order directing all residents to shelter at home and limit movements outside of their homes beyond essential needs. Many

businesses were closed and employees who could work from home were instructed to do so. Toll Collectors were now at risk of being exposed to the virus while performing their jobs. The PA Turnpike decided to cease cash collections to protect employees

and customers and on March 16, 2020, converted to All-Electronic Tolling (AET). The original intent was to honor the AET conversion planned for October 2021 and return to a cash system collection system after the pandemic. No one could have known

the magnitude of the epidemic. PA Turnpike traffic plummeted by almost 50% by the end of May and revenues dropped by more than $100 million. On June 2, 2020, the PA Turnpike announced that it would permanently remain in AET. It was evident

that returning to a cash collection system was too risky. Several factors influenced the landmark decision. With drivers now accustomed to traveling through Toll Points without stopping, going back to a cash system would be dangerous for drivers and

toll collectors. If a collector were to test positive for the virus, the interchange would shut down leaving a gap in the ticket/cash system and the PA Turnpike could not operate under those circumstances. The 2010s saw the advancement of two projects, Phase 2 of the Mon/Fayette Expressway – Uniontown to Brownsville Project and the groundbreaking for the second section of the Southern Beltway, the U.S. Route

22 to I-79 project. Reconstruction across the PA Turnpike continued and the roadway saw new grading, new drainage systems, new pavement, new guide rails, and a new median widened to 18 feet. Larger shoulders allowed easier access for emergency vehicles.

Environmental awareness expanded. The original concrete from highway reconstruction was recycled to provide a base for the new highway. The main administration building’s electrical needs were purchased from wind-generated power facilities.

The 2010s saw the advancement of two projects, Phase 2 of the Mon/Fayette Expressway – Uniontown to Brownsville Project and the groundbreaking for the second section of the Southern Beltway, the U.S. Route

22 to I-79 project. Reconstruction across the PA Turnpike continued and the roadway saw new grading, new drainage systems, new pavement, new guide rails, and a new median widened to 18 feet. Larger shoulders allowed easier access for emergency vehicles.

Environmental awareness expanded. The original concrete from highway reconstruction was recycled to provide a base for the new highway. The main administration building’s electrical needs were purchased from wind-generated power facilities. By the 21st century the original 160-mile route had expanded to 514 miles. The decade from 2000-2010 saw an increase in the use of intelligent devices to monitor the roadway and travel conditions. Roadway cameras,

a highway advisory radio system, a truck rollover and height alert system, fog detection system, a traffic flow detection system, and weather stations were put in place along the PA Turnpike. The PA Turnpike Commission started its public information program, TRIP,

which alerted the public to travel conditions via web, phone, email, and text messages.

By the 21st century the original 160-mile route had expanded to 514 miles. The decade from 2000-2010 saw an increase in the use of intelligent devices to monitor the roadway and travel conditions. Roadway cameras,

a highway advisory radio system, a truck rollover and height alert system, fog detection system, a traffic flow detection system, and weather stations were put in place along the PA Turnpike. The PA Turnpike Commission started its public information program, TRIP,

which alerted the public to travel conditions via web, phone, email, and text messages.

In 1985, the state legislature passed Act 61 which legislated that the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission complete route 60. The bill also assigned the Mon Fayette Expressway to the PA Turnpike.

In 1985, the state legislature passed Act 61 which legislated that the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission complete route 60. The bill also assigned the Mon Fayette Expressway to the PA Turnpike. In 1970, a plan was developed that involved updating the PA Turnpike’s original roadway through the Allegheny Mountains. This would be a road for the future, with the biggest part of the plan to include two lanes for cars

and two lanes for trucks on both sides of the roadway.

In 1970, a plan was developed that involved updating the PA Turnpike’s original roadway through the Allegheny Mountains. This would be a road for the future, with the biggest part of the plan to include two lanes for cars

and two lanes for trucks on both sides of the roadway. Although the PA Turnpike was one of the safest in the country, the need for more safety improvements became apparent in response to a rising number of crashes. Improvements included better pavement drainage and

stabilization, a 300-foot right-of-way, a 60-foot median, computerized Toll Points, plazas moved back away from the road, and curves added to the boring, straight stretches.

Although the PA Turnpike was one of the safest in the country, the need for more safety improvements became apparent in response to a rising number of crashes. Improvements included better pavement drainage and

stabilization, a 300-foot right-of-way, a 60-foot median, computerized Toll Points, plazas moved back away from the road, and curves added to the boring, straight stretches. The expansion project from Carlisle to Valley Forge opened on November 20, 1950, and ushered in a new decade of expansion. Extensions from Irwin to the Ohio Line and from Valley Forge to New Jersey soon followed.

But the Northeastern Extension, from Montgomery County in the south to Scranton in the north, was the longest of the expansion projects crossing some 110 miles.

The expansion project from Carlisle to Valley Forge opened on November 20, 1950, and ushered in a new decade of expansion. Extensions from Irwin to the Ohio Line and from Valley Forge to New Jersey soon followed.

But the Northeastern Extension, from Montgomery County in the south to Scranton in the north, was the longest of the expansion projects crossing some 110 miles.